Every brewer, whether amateur or professional, is well-acquainted with the challenges that come with maintaining brewing equipment. One such challenge is the pesky formation of beerstone. This stubborn substance can compromise the quality of the brew and pose sanitation issues. Let's delve deep into understanding beerstone and provide effective methods to eliminate it from brewing equipment.

What is Beerstone? A Deeper Dive into the Science

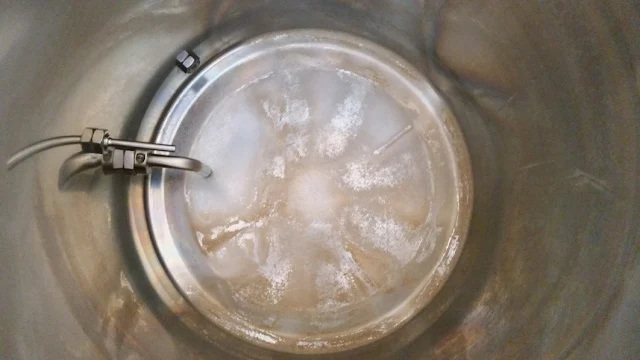

Beerstone, scientifically known as calcium oxalate, is a milky-white or sometimes brownish deposit that forms on brewing equipment over time. It's a combination of minerals, primarily calcium and magnesium salts, and organic compounds left over from the brewing process. If left untreated, beerstone can harbor microorganisms, jeopardizing the quality and safety of the brew.

The formation of beerstone is a classic example of precipitation chemistry. Oxalic acid, naturally present in malt, reacts with calcium ions found in the brewing water and the malt itself. This reaction forms calcium oxalate, a salt with very low solubility in water, especially under certain conditions. The chemical equation for this reaction is: $Ca^{2+}(aq) + C_{2}O_{4}^{2-}(aq) \rightarrow CaC_{2}O_{4}(s)$. The presence of proteins and other organic molecules in the wort acts as a "binder," helping the calcium oxalate crystals adhere to surfaces and creating a tenacious, difficult-to-remove scale.

Several factors can influence the rate of beerstone formation:

- Water Chemistry: Hard water, with its higher concentration of calcium and magnesium ions, is more prone to beerstone formation.

- Mash pH: The pH of the mash and wort can affect the solubility of calcium oxalate.

- Temperature: Temperature fluctuations during the brewing process, especially the rapid cooling of the wort, can cause calcium oxalate to precipitate out of solution.

Why is Beerstone a Concern for Brewers?

Beerstone is more than just an aesthetic issue; it's a serious concern for any brewer who values quality, consistency, and safety. Here's a more in-depth look at the problems it can cause:

- Sanitation Issues: The rough, porous surface of beerstone provides an ideal breeding ground for bacteria and wild yeast. These unwanted microorganisms can hide in the microscopic nooks and crannies of the beerstone, protected from routine cleaning and sanitizing procedures. This can lead to cross-contamination between batches, resulting in off-flavors, spoilage, and even potential health risks.

- Equipment Integrity: Over time, beerstone can cause significant damage to your brewing equipment. The buildup of this scale can lead to pitting and corrosion of stainless steel surfaces, reducing the lifespan of your expensive tanks, kettles, and other equipment.

- Inconsistent Brews: The presence of beerstone can interfere with the brewing process in several ways. It can act as a nucleation site, causing excessive foaming and gushing in the finished beer. It can also alter the flavor profile of your beer, leading to inconsistent batches and a product that doesn't meet your standards.

Effective Methods to Remove Beerstone: A Brewer's Guide

While beerstone can be a stubborn foe, it's not invincible. With the right knowledge and a consistent cleaning regimen, you can keep your equipment pristine and your beer delicious. Here's a step-by-step guide to effective beerstone removal:

1. Routine Cleaning: The First Line of Defense

The best way to deal with beerstone is to prevent it from building up in the first place. A thorough cleaning after every brew is essential. Use a high-quality, brewery-approved alkaline cleaner to remove organic soils like proteins and hop resins. Scrub all surfaces with a non-abrasive pad, paying close attention to hard-to-reach areas. This will remove the "binder" that helps beerstone adhere to surfaces.

2. The Power of Acids: Dissolving the Mineral Scale

For existing beerstone buildup, an acidic cleaner is your best weapon. Phosphoric acid and nitric acid are both highly effective at dissolving the calcium oxalate that makes up the bulk of beerstone. These acids work by breaking down the mineral scale and allowing it to be easily rinsed away. When using acidic cleaners, always follow the manufacturer's instructions for dilution and contact time. Be sure to wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves and eye protection, as these acids can be corrosive.

3. Specialized Beerstone Removers: A Targeted Approach

For tough, built-up beerstone, a specialized beerstone remover may be necessary. These products are formulated with a blend of acids, surfactants, and chelating agents that work together to break down and remove even the most stubborn deposits. They are often designed for specific applications, such as cleaning-in-place (CIP) systems, and can be a valuable tool in any brewer's arsenal.

4. Prevention is Key: Keeping Beerstone at Bay

Once your equipment is free of beerstone, you'll want to keep it that way. Here are some preventative measures you can take:

- Water Treatment: If you have hard water, consider using a water softener or reverse osmosis (RO) system to reduce the mineral content of your brewing water.

- Regular Acid Washing: Incorporate a regular acid wash into your cleaning regimen. This will help to prevent the buildup of beerstone and keep your equipment in top condition.

- Passivation: After cleaning with an acidic cleaner, it's a good idea to passivate your stainless steel equipment. This process creates a protective layer on the surface of the steel that helps to prevent corrosion and beerstone formation.

Safety First: A Brewer's Responsibility

When using chemical agents to clean brewing equipment, it's paramount to prioritize safety. Always:

- Wear protective gloves and eyewear.

- Ensure adequate ventilation in the cleaning area.

- Thoroughly rinse equipment after cleaning to remove any residual chemicals.

- Store cleaning agents out of reach of children and pets.

Conclusion: A Clean Brewery is a Successful Brewery

Beerstone is an inevitable challenge faced by brewers. However, with consistent cleaning, preventive measures, and the right cleaning agents, it's a challenge that can be efficiently tackled. By keeping brewing equipment free of beerstone, brewers can ensure the production of high-quality, consistent, and safe brews. Remember, a clean brewery is a successful brewery. Happy brewing!